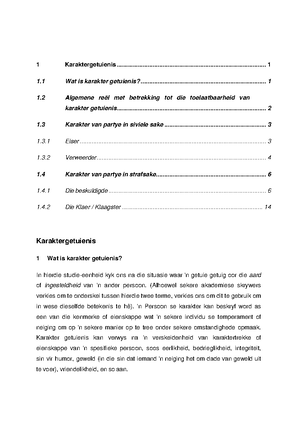

- Information

- AI Chat

DPP v Boardman [1975] A.C. 421

Law of evidence (BWR 300)

University of Pretoria

Recommended for you

Preview text

A. Rose Hall Ltd. v. Reeves (P.) they will humbly so advise Her Majesty. The appellant must pay the A costs of the appeal.

Solicitors: Charles Russell & Co.; Druces & Attlee.

R. W. LS.

B

[HOUSE OF LORDS]

DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS . . RESPONDENT AND ^ BOARDMAN APPELLANT

[On appeal from REGINA V. BOARDMAN]

197 4 April 9, 10; Orr L., Brabin and Stocker JJ. May D July 24, 25, 29, 30; Lord Morris of BorthyGest, Lord Wilberforce, Nov. 13 Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone, Lord Cross of Chelsea and Lord Salmon

Crime — Evidence — Corroboration — Homosexual offences against boys —" Similar facts " — Striking similarity of other offences to those with which charged — Whether evidence of " similar facts " admissible — Whether prejudice to accused outweighed by pro- E bative force — Sexual or homosexual offences — Whether special rule The appellant, the headmaster of a boarding school for boys, was charged with, inter alia, buggery with S, a pupil aged 16, and inciting H, a pupil aged 17, to commit buggery on him. At the trial, the judge ruled, and directed the jury, that the evidence of S on the count concerning him was admissible as p corroborative evidence in relation to the count concerning H, and vice versa. The jury convicted the appellant, and his appeal against conviction on the counts concerning S and H on the ground, inter alia, that the judge's ruling as to the admissibility of the boys' evidence had been wrong was dismissed by the Court of Appeal. On appeal by the appellant: — Held, dismissing the appeal, that there were circumstances Q in which, contrary to the general rule, evidence of criminal acts on the part of an accused other than those with which he was charged became admissible because of their striking similarity to other acts being investigated and because of their resulting probative force; that it was for the judge to decide whether the prejudice to the accused was outweighed by the probative force of the evidence and to rule accordingly; and that, on the facts of the present case, the judge had been entitled to direct the TT jury as he had done (post, pp. 439GH, 441B, DE, 442D, 444DE, a G—445B, DE, 452F—453E, 455DH, 457CD, 461BC, 462BD, 463AC). Dicta of Lord Herschell L. in Makin v. Attorney-General for New South Wales [1894] A. 57, 65, P, Lord du Parcq

Reg. v. Boardman (C.) [1975] in Noor Mohamed v. The King [1949] A. 182, 192, P. and Viscount Simon in Harris v. Director of Public Prosecutions A [1952] A. 694, 705, H.(E.) and Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729 , H.(E.) applied. Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 531 , CCA. considered. Per curiam. There is no special rule applicable to sexual or homosexual cases (post, pp. 441BC, 443E, 455H, 458c, 461G). Per Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone and Lord Cross of Chelsea. There is no logical distinction to be drawn between ™ " innocent association" cases and cases of complete denial (post, pp. 452FG, 458DF). Per Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone and Lord Cross of Chelsea. Where the general rule is held to be applicable in a case of this kind it should be given effect to by separate trials of the various counts (post, pp. 447CD, 459DE). Decision of the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division), post, p. 424), affirmed. Q

The following cases are referred to in their Lordships' opinions:

Advocate, H. v. A., 193 7 J. 96. Harris v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1952] A. 694; [1952] 1 All E. 1044, H.(E.). Makin v. Attorney-General for New South Wales [1894] A. 57, P. Maxwell v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1935] A. 309, H.(E.). D Moorov v. H. Advocate, 193 0 J. 68. Noor Mohamed v. The King [1949] A. 182; [1949] 1 All E. 365, P. Ogg v. H. Advocate, 193 8 J. 152; 1938 S.L. 513. Reg. v. Campbell [1956] 2 Q. 432; [1956] 3 W.L. 219; [1956] 2 All E. 272, CCA. Reg. v. Chandor [1959] 1 Q. 545; [1959] 2 W.L. 522; [1959] 1 All E. 702, CCA. E Reg. v. Flack [1969] 1 W.L. 937; [1969] 2 All E. 784, C. Reg. v. Hester [1973] A. 296; [1972] 3 W.L. 910; [1972] 3 AH E. 1056 , H.(E.). Reg. v. Horwood [1970] 1 Q. 133; [1969] 3 W.L. 964; [1969] 3 All E. 1156; 53 Cr.App. 619, C. Reg. v. Kilbourne [1972] 1 W.L. 1365; [1972] 3 All E. 545, C.; [1973] A. 729; [1973] 2 W.L. 254; [1973] 1 All E. 440, H.(E.). F Reg. v. Robinson (1953) 37 Cr.App. 95, CCA. Reg. v. Straff en [1952] 2 Q. 911; [1952] 2 All E. 657; 36 Cr.App. 132, CCA. Rex v. Bailey [1924] 2 K. 300; 18 Cr.App. 42, CCA. Rex v. Baskerville [1916] 2 K. 658, CCA. Rex v. Manser (1934) 25 Cr.App. 18, CCA. Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 531 ; [1946] 1 All E. 697, CCA. r Rex v. Smith (1915) The Trial of George Joseph Smith, edited by Eric R. Watson, Notable British Trials Series (1922); 11 Cr.App. 229, CCA. Thompson v. The King [1918] A. 221, H.(E.).

The following additional cases were cited in argument in the House of Lords: Reg. v. Morris (Raymond) (1969) 54 Cr.App. 69, C. H Reg. v. Rhodes [1899] 1 Q. 77. Rex v. Ailes (1918) 13 Cr.App. 173, CCA. Rex v. Ball [1911] A. 47, H.(E.).

Reg. v. Boardman (C.) [1975]

was capable of amounting to corroboration on count 1 and vice versa as the defence raised was not a specific defence which could be rebutted by similar fact evidence, but had been one of denial of the alleged incidents, and that the judge had erred in law in stating that because the type of behaviour alleged in each of counts 1 and 2 was of a particular or unusual kind therefore such evidence was mutually corroborative; (3) that the judge erred in law in directing that the evidence of a Mrs. Cole and a Police Inspector Baker was capable of amounting to corroboration on count 1 g since the evidence of neither witness connected the defendant with the crime charged in a material particular; (4) that the judge erred in law in directing the jury that the evidence of a Mr. Brough was capable of amounting to corroboration on count 3 since the evidence did not connect the defendant with the crime charged in a material particular in that: (a) Mr. Brough's evidence of seeing the complainant looking distressed did not relate to the incident which was the subject of count 3, and (b) the ^ evidence of seeing A looking distressed was equally consistent with the defendant's version of that day's incident as with A's version; (5) that the jury's verdict on count 3 was unsafe because as it was an offence of a sexual nature A's evidence as a matter of practice required corroboration and there was no such corroborative evidence on count 3. The facts are stated in the judgment. D

Gerard Wright Q. and Anthony Ansell for the defendant. Robert Ives for the Crown.

The arguments appear sufficiently from the judgment of the court.

Cur. adv. vult. E

May 13. ORR LJ. read the following judgment of the court. On July 3, 1973 , at Norwich Crown Court, the defendant was convicted, in each case by a majority of 11 to one, of an offence of attempted buggery (charged in count 1) and two offences of inciting the commission of buggery (counts 2 and 3). He was sentenced to three years' imprisonment on p count 1 and 18 months' imprisonment on each of the other two counts, all those sentences to run concurrently. He now, with the leave of the full court, appeals to this court against those convictions. At the material times the defendant was the headmaster of a language school in Cambridge in which a number of boys from overseas were pupils and the three offences involved three different pupils at that school. The first count charged him with the offence of buggery with a boy, S, 16 years of Cr age at the time, and on that count he was found not guilty of buggery but guilty of attempted buggery. The prosecution evidence was that that offence took place about midNovember 1972 in the defendant's sitting room at school where the defendant, after removing his own trousers and pants and those of S, sucked S's penis until he obtained an erection and then put S's penis against his own backside. There was evidence of JJ previous overtures by the defendant to S, the first in June 1972 in Tehran where S had gone home for his holidays and where the defendant was staying in a hotel. The defendant, according to S, put his hand on S's

A. Reg. v. Boardman (C.) private parts over his trousers. In September 1972, after S's return to school, according to S, the defendant said, " I want you to fuck me," and on a subsequent occasion in the television room in the school the defendant made a similar request. There had also, according to S, been an occasion when the defendant pleaded with him for five minutes of his time. The defendant was interviewed by Police Inspector Baker on January 26, 1973, when, according to the inspector's evidence, S's statement was read over to B him. He continually interrupted saying it was lies and alleged that S was lying because he, the defendant, had expelled him. The second count of inciting the commission of buggery involved another pupil, H, who at the time was 17 years of age. His evidence was that in January 1973 the defendant, after talking to H about his association with a girl, said, " Would you go upstairs and sleep with me?," which H refused. The defendant produced some whisky, which they drank, and after some further talk about the girl friend put his hand on H's private parts over his trousers. He again asked H to sleep with him and said, " If you don't want to fuck me, you can just lie on me." According to H there had been a previous incident when the defendant awakened him in the evening and took him in a taxi to the Taboo Disco Club where he bought him brandy. On their return to the school from that club the defendant D talked to him about sex and touched his private parts over his trousers. The defendant said, " Come and try it with me," and later said, " Come on and sleep with me, you needn't do it if you don't like it. Just sleep only." Count 3 involved another boy, A, 18 years of age. His evidence was that in September or October 1972 he was called into the defendant's office when the defendant complained of loneliness and said, " Let me make love with you." When A refused he said, "Please, I need you, I have no E friends." The following day A was going to telephone his father. The defendant said that if he did he, the defendant, would tell his father that A was a " queer." A did telephone his father and the defendant kept saying to the father, " Don't believe him." In January 1973, according to A, there was an occasion when the defendant was drunk and sent for him. He said, " You must understand that I love you." He also said, " Help me, p I want to make love with you. You are just as queer as I am, you want someone to fuck you." A left the room and shortly afterwards was seen by Mr. Brough, a teacher, who formed the view that he was in a distressed state. The inspector gave evidence that on March 27, 1973, the defendant said that he was making telephone calls to the fathers of those boys and he guaranteed that he, the inspector, would not finish up with one witness G except S. He said that if there were no witnesses, there would be no corroboration. The defendant in his own evidence denied committing any of the alleged offences or making any indecent overtures. He claimed that S had threatened him with a homosexual charge because the defendant had found S lying on a bunk in the dormitory on top of another boy. He claimed he JJ had taken H to the disco club because he wanted to confront him with a bad woman with whom he was associating. He claimed that A was lying because of a row there had been over missing money from the tuck shop and another about whether A should be allowed to have a car. He denied

A. Reg. v. Boardman (C.) Mr. Wright urged us not to put a construction on the speeches in Reg. v. A Kilbourne [1973] A. 729 which would reduce the ambit of the first of

these sentences in Makin's case, but in Harris v. Director of Public Prosecu- tions [1952] A. 694, 705, Viscount Simon indicated that in his view the classes of case mentioned in the second sentence did not constitute a closed list, and those classes have in fact been added to since Makin's case was decided. B In Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 531, the judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeal includes the following passages, at pp. 539540, 544:

" The evidence of each man was that the accused invited him into the house and there committed the acts charged. The acts they describe bear a striking similarity. That is a special feature sufficient in itself to justify the admissibility of the evidence; . . . The probative force C of all the acts together is much greater than one alone; . . . We do not think that the evidence of the men can be considered as corrobor ating one another, because each may be said to be an accomplice in the act to which he speaks and his evidence is to be viewed with caution; . . ."

The second of those passages was followed in Reg. v. Campbell [1956] D Q. 432 where, however, the view was expressed that, although the evi dence in question could not amount to corroboration, the jury might properly be told that a succession of similar cases might help them to determine the truth of the matter; but in Reg. v. Chandor [1959] 1 Q. 545 and Reg. v. Flack [1969] 1 W.L. 937 it was held that such a direc tion was improper where the defence was that the meeting or occasion for an incident in question did not take place at all. E In Reg. V. Kilbourne [1972] 1 W.L. 1365, which involved homosexual offences on boys belonging to two different groups, this court, being satis fied that each of the accusations indicated that the defendant was a man whose homosexual proclivities took a particular form and further that the evidence of each boy went to rebut the defence of innocent association which the defendant had put forward, held that evidence from boys in F either group as to alleged offences involving them was admissible in rela tion to the charges involving members of the other group but, on the authorities above referred to, was incapable of amounting to corroboration and, because the judge's direction could have led the jury to think that it was they quashed the conviction. On the second of these issues the House of Lords, rejecting the distinc tion previously drawn between evidence capable of amounting to corrobora ^ tion and evidence not so capable but as to which the jury could be directed that it might help them to determine the truth of the matter, took a different view and restored the convictions. In the House of Lords it appears that the issue as to the admissibility of the evidence was (at least eventually) conceded on behalf of the accused, but it is clear from the speeches that the House examined the relevant JJ authorities, from Makin's case onwards, in some depth (Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729, 741, per Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone L.) and con sidered it necessary to do so as a basis for considering the issue of corrobora tion (at p. 758, per Lord Simon of Glaisdale), and it is in our judgment

Reg. v. Boardman (C.) [1975]

clear that the House considered the evidence in question to be admissible not only to rebut the defence of innocent association but also because of its inherent probative value; in other words, on the basis of the first passage above quoted from the judgment in Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 531, 539. We base this conclusion in particular on passages in the speech of Lord Hailsham L. (with which Lord Morris of BorthyGest agreed), at pp. 74 1 and 742746, in Lord Reid's, at pp. 751 and 752, and in Lord Simon's, at pp. 75 4 and 758. B For these reasons we hold that Mr. Wright's main argument on this issue fails, but he advanced a further argument that the evidence in ques tion was inadmissible on the basis of the view expressed by Lord Reid in Kilbourne's case [1973] A. 729, 751 that only two instances would not be enough to make a system. But, with great respect to this view, we can find no support for such a restriction in any of the other speeches and indications that three of the other members of the House did not accept it, for Lord Hailsham L. (with whose speech Lord Morris, as already mentioned, agreed, and whose citation of the Scottish cases Lord Simon considered helpful) cited with approval, at p. 743, a direction by Lord Aitchison, the Lord JusticeClerk, in the Scottish case of H. Advocate v. A., 1937 i 96 , 98109 in which the evidence of only two girls was involved. In these circumstances we do not consider that we should be D justified in concluding that a majority of the House accepted Lord Reid's restriction as applying to admissibility, as distinct from weight, of evidence: see also, on this question, Reg. v. Wilson (1973) 58 Cr.App. 169. Mr. Wright next attacked a direction given by the judge with reference to certain evidence given by Inspector Baker and by the defendant at the trial. The inspector's evidence was that when he interviewed the defendant and read to him a statement by S the defendant said, " It's all lies, he only said this because I expelled him." In his own evidence the defendant denied saying to the inspector that he had expelled S but agreed that he had not in fact expelled him and said that the reason why S had told lies was that the defendant had caught him in a homosexual act with another boy, and S had then threatened to implicate the defendant unless he kept quiet about it. F In relation to that evidence the judge directed the jury that if they were satisfied that the defendant had lied, either to the police before the trial or in the witness box, such lies were capable of amounting to corroboration. Mr. Wright has attacked this direction on the grounds that if the defendant lied to the inspector it was only on a peripheral matter and that, on the authority of Reg. v. Chapman [1973] Q. 774, lies told by the defendant in evidence at the hearing cannot amount to corroboration. We are unable ® to accept the first of these arguments. In our view if the defendant lied to the inspector in saying that he had expelled S it was not a lie on a peri pheral matter but " '. . . of such a nature, and made in such circumstances, as to lead to an inference in support of the evidence of [the com plainant] ' . . .": see Credland v. Knowler (1951) 35 Cr.App. 48, 55, citing Dawson v. M'Kenzie (1908) 45 S.L. 47 4 and Jones V. Thomas JJ [1934] 1 K. 323. As to lies by the defendant in court we accept the correctness of the decision in Reg. v. Chapman [1973] Q. 77 4 on the facts of that case, and that it will be applicable in most cases.

Reg. v. Boardman (C.) [1975]

It was pointed out in Reg. v. Redpath (1962) 46 Cr.App. 319, 321, that in considering observed distress as possible corroboration A

" the circumstances will vary enormously, and in some circumstances quite clearly no weight, or little weight, could be attached to such evidence as corroboration "

and in Reg. v. Luisi [1964] Crim.L. 605, where the court considered that the significance of a girl's distress had been overemphasised, it was g indicated that wherever the possibility exists of the distress being feigned a careful warning should be given to the jury on that subject. We have found this ground of appeal a difficult one. On the one hand it cannot be said that the judge overemphasised the aspect of distress. On the other hand the distress was not directly associated with the incident which was the subject of count 3; it seems difficult to exclude the possibility of its being feigned; and there was no other evidence capable of supplying C corroboration. We have come to the conclusidn that the distress should either not have been put to the jury at all or, if put, should at least have been accompanied by a warning as to the possibility of its having been caused otherwise than by an indecent suggestion made by the defendant or by a row with him, which were the two alternatives left to the jury in the summing up; and because this count, in the respects already mentioned, _. stands on its own and no other corroboration was available, we do not consider it safe to apply the proviso to section 2 (1) of the Act of 1968. In the result the conviction on count 3 will be quashed, but the appeal fails on counts 1 and 2. Appeals against counts 1 and 2 dis- missed; appeal against count 3 allowed. Certificate under section 33 (2) of the ^ Criminal Appeal Act 1968 , that a point of general public importance was in- volved in the decision, namely: " whether on a charge involving an allegation of homosexual conduct there is evidence that the accused person is p a man whose homosexual proclivities take a particular form, that evidence is thereby admissible although it tends to show that the accused has been guilty of criminal acts other than those charged." Leave to appeal refused. "

Solicitors: Bobbetts, Harvey & Grove, Bristol; Director of Public Prosecutions. P. R. K. M.

June 20, 1974. The Appeal Committee of the House of Lords (Lord JJ Diplock, Viscount Dilhorne and Lord Kilbrandon) allowed a petition by the defendant for leave to appeal. The defendant appealed.

A. Reg. v. Boardman (H.(E.)) Gerard Wright Q. and Anthony Ansell for the defendant made sub "■ missions with regard to the question for the consideration of the House. The classic exposition of the law is by Lord Herschell L. in Makin v. Attorney-General for New South Wales [1894] A. 57. [Reference was made to Rex v. Ball [1911] A. 47; Maxwell v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1935] A. 309, per Viscount Sankey L, at p. 317 and Harris v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1952] A. 694, 702.] In most B cases since Makin the courts have accepted that the " first leg " of Lord Herschell's statement at p. 65 is an exclusionary canon, and have explained what kind of evidence of criminal conduct or disposition becomes admissible because of the issue before the jury. In Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 531 the , Court of Criminal Appeal departed from the basic principle of Makin and, while paying lip service to the " first leg," in fact ignored it. So in Sims there was a radical departure from what had been accepted to be the law. C It was wrongly decided, and any subsequent decision founded on it is unreliable and ought to fall with it. Where the accused's defence is not of innocent association but simply that he was not there, the evidence of similar conduct is inadmissible. The following propositions as to the law are made. (1) The " first leg " of Lord Herschell's statement in Makin sets out a general exclusionary £> canon relating to similar fact evidence, because it is evidence tending to show that the accused has been guilty of criminal acts other than that alleged in the charge in question. (2) This is solely because of the inherent prejudice in such evidence, not because such evidence is not both probative and relevant. In the context of this second proposition the statement of Lord Simon of Glaisdale in Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729, 757 is adopted in its entirety, though it is the E opposite of what Lord Sumner said at one stage in Thompson v. The King [1918] A. 221, 232. (3), which goes to the "second leg" of Lord Herschell's statement in Makin, in certain circumstances, where the similar fact evidence has high probative value otherwise than by leading to the conclusion that the accused is a person likely from his criminal conduct or character to have committed the offence in question, p the courts exceptionally admit this particular evidence: see Rex v. Smith (1915), Notable British Trials Series (1922). (4) The list of such circumstances is not closed. The process of reasoning involved in deciding whether a given set of circumstances fits within the second rather than the first leg of Makin is to decide whether the probative value to an issue in the case outweighs the prejudice unleashed when the evidence is revealed to the jury. In the context of this proposition, see the judgment G of O'Connor J. in Reg. v. Horwood [1970] 1 Q. 133, 137 et seq. (5) Examples of the process of reasoning being applied where the probative value is greater than the prejudice are classified (as they must be) as follows: (i) where the issue is to show identity: Thompson v. The King [1918] AC. 221 ; Reg. v. Robinson (1953) 37 Cr.App. 95; Reg. v. Straffen [1952] 2 Q. 911; Reg. v. Morris {Raymond) (1969) 54 Cr.App. 69. JJ (ii) Where the issue is to rebut mistake or accident: Rex v. Smith (1915); Reg. v. Rhodes [1899] 1 Q. 77. (iii) Where the issue is to show intent: Rex v. Ball [1911] A. 47. (6) (a) What is common to the examples in (5) is that one does not infer guilt directly from the similar fact evidence—

A. Reg. v. Boardman (H.(E.)) A question which may be posed is whether, when there is more than A one allegation of homosexual conduct in a particular form, e. as a catamite, the evidence in support of those allegations is mutually admissible being admissible per se because the allegations are of similar conduct. The following propositions arising out of Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 53 1 are made: (1) in view of Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729 a succession B of strikingly similar allegations may in an appropriate case be classified as corroborative, but before they can be used as corroboration they must first be admissible without infringing the rules to be derived from Makin v. Attorney-General for New South Wales [1894] A. 57; (2) admitted or proved criminal acts may not be given in evidence for the purpose of showing that the accused is likely to have committed the offence; (3) a fortiori, is not permissible to offer proof of an alleged criminal act for the C like purpose. As to (1), it was said in Sims that the probative force of more than one allegation is greater than that of one allegation. If, however, one cannot bring in a conviction of an offence with X in connection with an offence charged with Y, one cannot possibly bring in the mere allegation. [Reference was made to Reg. v. Kilbourne (Court of Appeal) [1972] 1 W.L. 1365.] D The appeal in Kilbourne related to corroboration, not to the admissibility of the evidence. It had already been decided that it was admissible: see per Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone L. [1973] A. 729, 741. All the members of the House were accepting that it was admissible. The defen dant accepts the correctness of two decisions in the Court of Appeal which support what he is submitting: Reg. v. Chandor [1959] 1 Q. 545 (Court of Criminal Appeal) and Reg. v. Flack [1969] 1 W.L. 937. E In summary, the pattern of decisions in the realm of similar fact evidence has been to categorise ways or headings under which similar fact evidence can be admitted under the second leg of Makin v. Attorney - General for New South Wales [1894] A. 57. The House in Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729 was considering the question of corroboration. There has never been any decision of the courts where similar fact evidence p was admitted only to corroborate. In Kilbourne the House cannot have decided that the evidence was admissible for that purpose, because in each one of the speeches the evidence was accepted as admissible before the question of corroboration was considered. The issue before the House here is: may one in appropriate circumstances—a matter of discretion— admit evidence of similar facts to corroborate a witness and for no other reason? Viscount Simon in Harris v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1952] G A. 694, 705 said that the categories were not closed. If one examines virtually any of the previous decisions where similar fact evidence was admitted, almost invariably the evidence could be used to corroborate a witness in the case, but that has never been the ground of decision. To introduce evidence merely to corroborate must be in breach of the first leg of Lord Herschell's statement in Makin v. Attorney-General for New South JJ Wales [1894] A. 57, 65, because if incident A be proved one can then sometimes infer the truth of an allegation of incident B, but one does so because incident A indicates a propensity in the accused to do what is alleged in incident B. It makes no difference whether incident A is proved

Reg. v. Boardman (H.(E.)) [1975]

fact, admitted fact, inferred fact or a fact alleged in the case. The logical process must always be the same. " Proved means evidence proved in the " case or already proved so as to be res judicata and so proved in the trial (issue estoppel). If that be right, then the evidence adduced here to corro borate must be in breach of the first leg in Makin. That follows because of the purpose for which it was admitted. There is a difference of approach in the Scots cases, where plainly what is said in the passage quoted from H. Advocate v. A., 193 7 J. 96 by B Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone L. in Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729 , 745746 is not peculiar to that particular summing up or exceptional but general; it is a rule of Scots law. As to the facts here, the purpose behind the admission of strikingly similar facts was to corroborate. It was sought to use them as corrobora tion. The principles in Reg. v. Kilbourne must be applied to the facts. There is no English authority before Kilbourne in which this aspect of C corroboration has been considered, that is, where two witnesses are speak ing to entirely separate incidents and it is sought to use their evidence as mutual corroboration. It was because there was no English authority that the House in Kilbourne prayed Scots law in aid. How can the " rule in Moorov's case " [Moorov v. H. Advocate, 193 0 J. 68] be applied to the present case? See Ogg v. H. Advocate, 193 8 J. 152 in relation p specifically to the facts here. The offence with S was charged between October 1 and November 30, 1972. The evidence never purported to put it any closer than that. That shows that it took place in one particular term, followed by the Christmas holidays. It also took place late at night. The offence with H was charged on January 14, 1973, in an entirely separate term. If one looks at the Scots cases, they do appear to apply a far stricter E test with regard to relevance than English law hitherto has done. Sir Michael Havers Q. and Robert Ives for the Crown referred to the evidence regarding " ganging up " and with regard to S. In Ogg v. H. Advocate, 193 8 J. 152 there was no history, no long period of time, no build up. Here, there was a history and a build up. Nowadays, the practice of the prosecution where there are a series of suspected offences is to allege p the first, the last and the worst. If that had not been done in this case, the other matters relied on by the prosecution could have been the subject of charges. The Crown does not seek to argue that homosexuality as such is ever sufficient of itself to justify similar fact evidence. Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 531 was understood by some to make the fact that acts were homosexual a sufficient nexus, and one got the impres ^* sion, perhaps fostered by university professors, that it was more a " pro pensity " than a true " similar facts " case. There were striking similar facts, whereas Reg. v. Chandor [1959] 1 Q. 545, for example, was just a typical case of an assault by a schoolmaster on a boy. Lord Simon of Glaisdale in Reg. V. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729 was right when he said, at p. 757, that all relevant evidence was admissible unless excluded JJ on grounds of prejudice. In each case the evidence is admissible because it tends to show not only that the accused has done exactly the same thing on another occasion but also that what he did was

Lord Morris Reg. v. Boardman (HX.(E.)) [1975] of Borth-y-Gest b \ \ > r in support of the submission was that it was unsafe to leave the charge to , the jury because S's evidence was unsatisfactory. The learned judge held that the quality of S's evidence was a matter for the jury to assess. The second ground was that the evidence directed to counts other than count was not capable of being admissible to assist in proving count 1 and that the evidence on count 1 was itself insufficient and unsatisfactory. The learned judge proceeded to indicate both the way in which he ruled and the way in which he would eventually direct the jury. He said that the evidence B on count 2 was admissible on count 1 and that he so ruled on the basis of Rex v. Sims [1946] K. 531. He further said that the evidence would therefore also be capable of being corroborative evidence on count 1 and that he so ruled on the basis of Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729. Cor respondingly the evidence on count 1 would also be admissible on count and could provide corroboration. He ruled, however, that similar considerations did not apply in the case of count 3 which would stand on ^ its own. The evidence supporting the allegations of count 3 was not, he said, of sufficient precision to bring it within any principle relating to " similar facts " evidence. For an appreciation of the matters raised on appeal it is necessary briefly to summarise the evidence given respectively by S and by H and by the appellant as it was presented to the jury in the summing up. S spoke of a D number of incidents. The first occurred at Tehran before the autumn term of 1972 began. S had gone home for his holidays. The appellant was stay ing in Tehran in a hotel. According to S there was an indecent assault. As to that the appellant said that he had merely put his arm round S but had not put his hand on S's private parts. The second incident was at Cambridge when S said that the appellant had tried to touch him in the private parts but was repulsed. That incident the appellant denied. The third incident (which was at the end of September or beginning of October) occurred at about four or five in the morning when S was asleep and was awakened and felt something touch his face. S's evidence was that the appellant was there and said: " I love you, I love you, can you come to the sitting room for five minutes . . . five minutes of your time,. . ." As to this the appellant said that he was doing the rounds in the dormitory and saw F that S was not in his own top bunk but was in the bunk of another boy; that, kneeling down, and speaking quietly so as not to awaken other boys, he told both to go to the sitting room saying that he would only keep them for a short time; that possibly he said five minutes; that the other boy pre tended to be asleep and that S refused to come; that he tried unsuccessfully three times to get S (who was very angry) to come. The appellant then left them. There was an interview next day. The next incident according to S was when the appellant asked him to go alone with him, offered him money " if you will be a very good friend of mine," knelt in front of him and made the specific request not only that buggery should take place but furthermore that S should play the active and the appellant the passive part. That incident the appellant denied. The next occasion was when the appellant said to S that he would tell the seniors not to go to the sitting room that JJ night and that S should come by himself. That was denied by the appellant. Then came the occasion when according to S the actual act of buggery took place. Some time after 10 p. the appellant had asked

A. Reg. v. Boardman (H.(E.)) . Lord Morris . S to go to him and had threatened him with expulsion "if tonight you don't do it on me." S later went to the appellant and in his evidence he described in some detail what took place. The appellant wholly denied the occasion. There was evidence given by a police officer and also by the appellant as to what was said during an interview between them in January 1973. This was material in regard to corroboration of S's evidence. B H gave evidence of two incidents. The first of these began when one night the appellant, at some time between midnight and 2 a., woke H who was asleep in a dormitory and told him to get dressed. Together they then went by taxi to a club called the Taboo Disco Club. After some drinks there they returned to the school and then sat drinking and talking in the sitting room. Then, while seated close together, the appellant according to Q H started to touch his (H's) private parts through his trousers; he asked H to sleep with him and made the specific suggestion that H should play the active part and he (the appellant) the passive part. As to all this the appellant's evidence was that he had taken H to the club but that that was in the hope of confronting H with a woman with whom he understood H had been associating and who was regarded by the appellant as being un desirable as an associate. The appellant denied that on their return to the D school he had made any indecent suggestion or invitation. The second incident spoken to by H was that which was the basis of count 2. It occurred on or about January 14, 1973. After an earlier discussion as to whether H should not (as the respondent wished) return to the school after the Christmas holidays as a boarder rather than (as H wished) as a day boy H said that while they were in the sitting room the appellant again asked H n to sleep with him and then touched his (H's) private parts. The evidence of the appellant was that after the Christmas holidays H had not returned to the school as a boarder but on his own initiative had become a day boy and was associating with an undesirable woman. The January interview related to that matter but the appellant said that there was no indecent gesture or indecent suggestion. After the summing up of the learned judge, to which I must more F particularly refer, the jury, by majority verdicts of eleven to one, convicted the appellant on count 1 of attempted buggery and convicted him on count 2 and on count 3. He appealed to the Court of Appeal. The conviction on count 3 was quashed. The learned judge had ruled that that count stood on its own. There was only one piece of evidence which was possibly capable of supplying corroboration in regard to the count; the Court of Appeal, Q having considered that evidence, felt that it either should not have been left to the jury at all or, if left, should have been accompanied by warnings which were not given. As to counts 1 and 2 the appeal failed and was dismissed. The court considered that the main questions raised on behalf of the appellant were covered by the decision in this House in Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729. Though leave to appeal was refused by the Court of Appeal, a point of law of general public importance was certified

H arising out of the dismissal of the appeal on counts 1 and 2. The point was expressed as being: " Whether, on a charge involving an allegation of homosexual conduct A. 1975—1 7

A. Reg. v. Boardman (H.(E.)). Lord Morris of Borth-y-Gest to which it is professedly directed to make it desirable in the interest of justice that it should be admitted. But at whatever stage a judge gives a ruling he must exercise his judgment and his discretion having in mind both the requirements of fairness and also the requirements of justice. The first limb of what was said by Lord Herschell L. in Makin's case was said by Viscount Sankey L. in Maxwell v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1935] A. 309 , 317 to express "... one of the most deeply rooted and jealously B guarded principles of our criminal law, . . ." Judges can be trusted not to allow so fundamental a principle to be eroded. On the other hand, there are occasions and situations in which in the interests of justice certain evi dence should be tendered and is admissible in spite of the fact that it may or will tend to show guilt in the accused of some offence other than that with which he is charged. In the second limb of what he said in Makin's case Lord Herschell gave certain examples. In his speech in Harris v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1952] A. 694 Viscount Simon pointed out, at p. 705, that it would be an error to attempt to draw up a closed list of the sorts of cases in which the principle operates. Just as a closed list need not be contemplated so also, where what is important is the appli cation of principle, the use of labels or definitive descriptions cannot be either comprehensive or restrictive. While there may be many reasons why D what is called " similar fact" evidence is admissible there are some cases where words used by Hallett J. are apt. In Reg.- v. Robinson (1953) Cr.App. 95 he said, at pp. 106107: " If a jury are precluded by some rule of law from taking the view that something is a coincidence which is against all the probabilities if the accused person is innocent, then it would seem to be a doctrine of law £ which prevents a jury from using what looks like ordinary common sense." But as Viscount Simon pointed out in Harris v. Director of Public Prose- cutions [1952] A. 694, 708 evidence of other occurrences which merely tend to deepen suspicion does not go to prove guilt: so evidence of " similar facts " should be excluded unless such evidence has a really material bearing p on the issues to be decided. I think that it follows from this that, to be admissible, evidence must be related to something more than isolated instances of the same kind of offence. Though certain passages in the judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeal in Rex V. Sims [1946] K. 531 have been disapproved, I am wholly unable to accept the argument now presented that the decision should be rejected. In Reg. v. Kilbourne [1973] A. 729, as Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone G L. pointed out in his speech, at p. 741, we examined in some depth the authorities between 1894 and 1952 in relation to the admissibility of " similar incidents " evidence. Though Kilbourne's case proceeded after an admission that the evidence under consideration was both admissible and relevant to the evidence requiring corroboration there was, in our decision, not only no rejection of but, on the contrary, an acceptance of what was JJ decided in Sims's case, i., that there are cases in which evidence of certain acts becomes admissible because of their striking similarity to other acts being investigated and because of their resulting probative force. There was in Kilbourne's case disapproval of what had been said in Sims's case in

Lord Morris Reg. v. Boardman (H.(E.) ) [1975] of Borth-y-Gcst " regard to corroboration. There was disapproval of the suggestion that a A certain variety of sexual offences can be put in a special category. In the earlier case in the Privy Council of Noor Mohamed v. The King [1949] A. 182 there was criticism of one passage in the reasoning of the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Sims's case. But the decision in Sims's case stands. Professor Cross in his book on Evidence, 3rd ed. (1967), p. 319, thus summarises the decision in Sims's case: " The similar fact evidence was admissible because there were specific features which made each accusation bear a striking resemblance to the others. The evidence showed, not merely that the accused was a homosexual, but also that he proceeded according to a particular technique; not only was the accused given to committing the crime charged, but he was also given to doing it according to a particular pattern." C

In Kilbourne's case the Court of Appeal had followed Sims's case in holding that the contested evidence was admissible. They said [1972] 1 W.L. 1365, 1369: "... each accusation bears a resemblance to the other and shows not merely that the appellant was a homosexual, which would not have been enough to make the evidence admissible, but that he was one D whose proclivities in that regard took a particular form."

They also held that the evidence of each boy went to rebut the defence of innocent association. They also said, at p. 1370: " What, for example, did Gary's evidence prove in relation to John's on count 1? The answer must be that his evidence, having the g striking features of the resemblance between the acts committed on him and those alleged to have been committed on John, makes it more likely that John was telling the truth when he said that the appellant had behaved in the same way to him."

Of the reasoning in these passages we indicated approval in Kilbourne's case. It was on the issue as to corroboration that we differed from the p Court of Appeal. The valuable citations from some of the Scottish cases contained in the speech of Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone L. give added support to the central reason for the decision in Sims's case. Thus in Moorov v. H. Advocate, 193 0 J. 68 there is reference to the existence of " an underlying unity, comprehending and governing the separate acts," (p. 73 ) and to " a certain peculiar course of conduct," (p. 89) and to " a close similarity between the nature of the two offences to each of which G only one witness speaks," (p. 92). So in H. Advocate v. A., 193 7 J. 96 there is a reference to finding a man " doing the same kind of criminal thing in the same kind of way towards two or more people," [per the Lord JusticeClerk (Lord Aitchison), at p. 99]. So in Ogg v. H. Advocate, 193 8 S.L. 513; 1938 J. 152 the trial judge had told the jury that while in general the mere fact that a number of similar offences are charged in „ one indictment does not make evidence with regard to any one charge available with regard to the others yet it may be otherwise if the acts are " closely related in time, in circumstance, and in character " (pp. 515; 159).

DPP v Boardman [1975] A.C. 421

Course: Law of evidence (BWR 300)

University: University of Pretoria

- Discover more from: